What About "Whataboutism"?

If you’ve participated in online political conversation over the past few years, you’ve likely encountered the term “whataboutism.” The term’s name is derived from its meaning, which Merriam Webster describes as the “act or practice of responding to an accusation of wrongdoing by claiming that an offense committed by another is similar or worse.” Rather than responding to the argument at hand, one might deflect an allegation with a response of “Well, what about [insert other event or act] that your side did?”

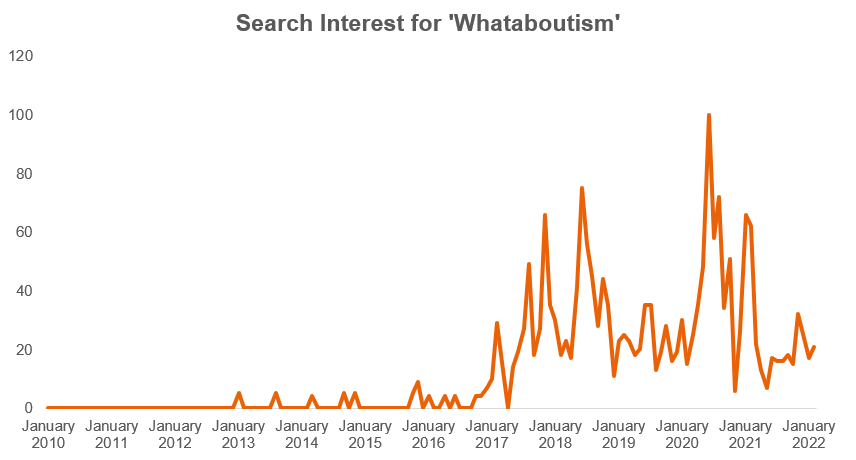

While the terms “whataboutism” and “whataboutery” have been used since at least the 1970s, it’s a relatively new addition to the vocabulary of the American public; the term only made its way into the Merriam Webster dictionary a few months ago in October of 2021.

So why has the term recently arrived on the scene? As the chart below shows, its emergence into the public vocabulary coincided neatly with the start of Donald Trump’s presidency January of 2017:

If you think back to Trump’s presidency, it isn’t terribly surprising that this term gained popularity during the period. Because Trump and his political allies regularly did awful things, his supporters often sought to deflect criticism by pointing to some other awful and ostensibly similar thing done by the other side. Famously, Trump himself did a classic bit of whataboutism in defense of Vladimir Putin:

Bill O’Reilly: “He’s a killer, though. Putin’s a killer.”

Donald Trump: “There are a lot of killers. We got a lot of killers. What, you think our country’s so innocent?”

As politically engaged individuals observed this strategy being used, they increasingly began to call it out under the label of whataboutism. “That’s just whataboutism,” one might respond to Trump’s remark above, alleging that Trump is simply deflecting rather than addressing the subject at hand.

But in the same way that whataboutism itself can be used to derail or deflect from a valid argument or claim, so too can an allegation of “whataboutism,” as others have noted:

Christian Christensen, Professor of Journalism in Stockholm, argues that the accusation of whataboutism is itself a form of the tu quoque fallacy, as it dismisses criticisms of one's own behavior to focus instead on the actions of another, thus creating a double standard. Those who use whataboutism are not necessarily engaging in an empty or cynical deflection of responsibility: whataboutism can be a useful tool to expose contradictions, double standards, and hypocrisy.

So how should we think about a given whataboutism and allegations of “whataboutism,” then? Should a reference to an ostensibly analogous situation that reveals hypocrisy be viewed as a deflection? Or a valid form of analogical argument? And what of an allegation of whataboutism? Is that a valid callout of a deflection? Or a deflection itself?

Unhelpfully, I believe the answer to each question above is “It depends.” Both a reference to another event to demonstrate hypocrisy and an allegation of “whataboutism” can be used in sound or unsound ways. If the analogy is being used as a deflection, than an allegation of “whataboutism” is fair. But if the analogy is being used to advance the conversation, an allegation of “whataboutism” then becomes the deflection (i.e., by refusing to engage with a sound argument).

How, then, can you know if the underlying analogy is being used as a deflection? One way to appraise the analogy would be on the actual merits. Is the analogy actually invoking a similar situation? Or is it only invoking a superficially similar situation that is dissimilar in important respects? But even if the analogy is a poor one, it’s not clear that the person you’re speaking with was trying to deflect; they may simply have mistakenly drawn a poor analogy, or there may be disagreements about the analogy’s applicability.

The difference, then, comes down to intent. Are they fundamentally trying to change the subject to avoid talking about the matter at hand? If so, it’s fair to flag that as whataboutism. But if they’re trying to use analogical reasoning to advance the conversation and demonstrate how you may agree with their logic under different circumstances, the whataboutism label does not apply.

Intent is often difficult to reliably discern, though, and especially so in the context of a disagreement. You may be inclined to think someone’s analogy is a deflection and that they’re operating in bad faith when, in fact, if you could climb into their head you would be surprised to learn that they feel strongly that they’re drawing a valid comparison that vindicates their viewpoint.

I think the best practice is to assume they’re operating in good faith (as I wrote about about here) and continue as if they are invoking the analogy to persuade you of the correctness of their position. This does not mean the analogy must be accepted; if it’s a poor analogy, explain why you believe it does not apply to the matter at hand. Perhaps they’ll have a rebuttal as to why it does. If they are arguing earnestly and you treat them as such, the conversation can proceed whereas it would have been cut short if you’d accused them of bad faith.

And if they are operating in bad faith, calling out a poor analogy as “whataboutism” doesn’t actually do much. It may be a correct assessment, but since they aren’t operating in good faith anyways there’s very little chance that the conversation will be productive regardless of what you say. Rebutting a poor analogy, even if they are arguing insincerely, is still a better response than just blurting “That’s whataboutism!”. You can always disengage later if you become confident that they are not conversing in good faith.

With all that, here’s my overall takeaway on whataboutism:

Allegations of “whataboutism” are not useful and we should stop throwing the term around. Analogical reasoning is a standard means of argument and the fact that someone attempts to invoke an analogy demonstrating hypocrisy should not be met with an accusation of a logical fallacy. Such an allegation is at least as likely as the underlying analogy to itself serve as a deflection or to short circuit the conversation. Instead, just take the analogy head on and address their point. If the analogy is poor, rebutting it should be no problem. And if they were simply attempting to deflect and are not engaging in good faith, you can always step back from the conversation at a later point. Whether someone is engaging sincerely or insincerely, accusing them of having committed a “whataboutism” is unlikely to be productive.

Note: I hope readers are able to make sense of this article. I found this a difficult topic to write about semantically as I was simultaneously discussing whataboutism for its meaning (i.e., drawing an analogy to point to your opponent’s hypocrisy) and “whataboutism” as used as an allegation. I plan to keep my eyes out for uses of “whataboutism” as an allegation and update this article with a few real world examples to help clarify.